How language activists across communities in Africa and Asia are countering digital safety threats and risks to their languages’ survival.

For 10 years, Adéṣínà Ghani Ayẹni, or Ọmọ Yoòbá, has been involved in numerous activities to rejuvenate the Yorùbá language. A digital language activist and founder of Yobamoodua Cultural Heritage — an organisation working towards the preservation and revitalisation of Yorùbá socio-cultural heritage — he has been conducting activities like websites localisation, content creation, and the archiving of the oral literature of the Yorùbá people. In Nigeria, Yorùbá language activists face many challenges in upholding the sovereignty of their language online, which affects their privacy and digital security. This includes the lack of access to digital security resources and education in the language, which limits their awareness of digital security threats and prevents participation in many online spaces.

These findings are documented in “Digital Safety Matters: A Case study of Yorùbá Language Speakers Online”. The research is part of the collaboration with Rising Voices, where 18 language activists from 18 different language communities investigated digital safety and security concerns affecting their communities. The accounts below reflect the challenges in online spaces by language activists, and the strategies to counter the threats and the risks to language survival.

Digital security threats experienced by language activists in West and East Africa

Ọmọ Yoòbá and Yorùbá activists are not alone in experiencing digital security threats. The Igbo Wikimedians User Group in Nigeria has been engaging in diverse efforts to make the Igbo language accessible in online environments. The group faces constant digital security and online safety challenges such as spamming, hacking, and defrauding. Due to the lack of digital safety and security resources in the Igbo language, the activists’ knowledge on how to guard themselves is limited, despite possessing general knowledge about digital security.

In Ghana, the Twi Language Wikimedians Group works to increase the presence of the Twi language online. It is through their committed strategies of content creation and translation that there is Twi translation available on Wikipedia. They also face challenges around spamming, hacking, impersonation, identity theft, and data extraction among the language communities. The slow and low-quality Internet services in the country also limit many users’ experiences online. All of these affect not only the economy and the daily lives of the citizens, but also language revitalisation processes. There are also no materials on digital security education in Twi.

In Kenya, poet Njeri Wangarî undertook a research project to understand the experiences of the digital lives of Indigenous Gîkûyû language activists. The Gîkûyû language has gone through many transformations — from the Kenyan airwaves on radio, through tv, and eventually making its way online after the country’s 2009 digital transformation. In the run-up to Kenya’s 2017 general election, social media was used to incite violence and hate speech. The use of local languages, such as Gîkûyû, was seen as failing to foster national unity in favour of one’s tribe. Thus, in the election year, an entourage of linguistic intolerance also took hold whenever politics take centre stage. The lack of representation of Gîkûyû online also led to limited access to translations and Gîkûyû-specific keyboards.

Language survival under threat in Asia

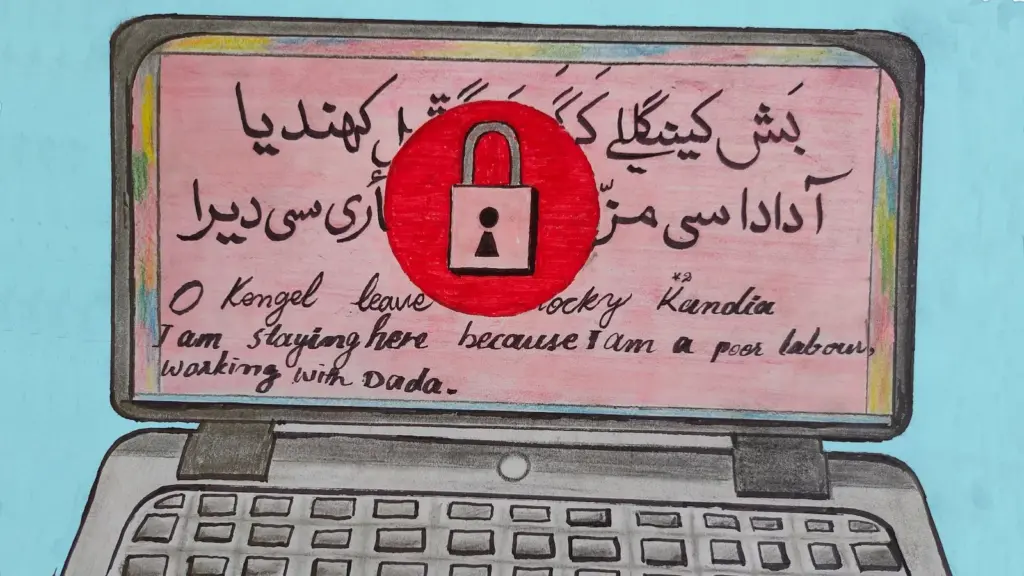

In Pakistan, the team of activists and researchers of Idara Baraye Taleem wa Taraqi (IBT) work to keep the Torwali language and culture alive. They use strategies like publishing and training using social media and digital tools. A language affected by the Pathan invasion, the Torwali language and culture faced severe extinction if not for the revitalisation initiatives by IBT. However, this created new challenges such as harassment, surveillance, and online threats. These are all amplified by the government’s control of the Internet environment, carrying out Internet shutdowns, blocking websites, and curbing free speech and criticism of the government. With the demonisation of NGOs in the country, IBT faces extra challenges, such as forced disappearances of activists, death threats, as well as the use of repressive laws to limit their freedom of expression.

In India, factors such as caste, gender, and economic strata contribute further to digital vulnerabilities among native Odia speakers. The Dalits — who are socially, economically and historically marginalised communities in the country — are structurally more limited in accessing and adopting technology compared to their dominant caste peers. They also would self-censor their activism as not to invite more scrutiny. Women in India also face significant limited access to information due to low linguistic literacy and English fluency, limited access to mobile devices, and lack of knowledge of (digital) safety and security. These factors result in the digital exclusion of women and increased vulnerability to safety risks. This exclusion is compounded for women from low-income groups and Dalit women, who often rely on other companions to navigate the English-majority digital sphere. The lack of Odia representation online reflects in the lack of digital content, translation, and interface localisation. Odia internet users are more vulnerable to misleading advertisements, in addition to spam calls and text messages asking for banking and other sensitive information.

Creative strategies to counter challenges

Despite these challenges, language activists work daily to keep their languages alive. In the face of language intolerance, closing civic space and the lack of language representation online, in-person and online language communities continue to innovate around sustaining the use, representation and enjoyment of their respective languages.

Eastern Tharu speakers are finding ways to conserve ‘Basghara’ culture through an inclusive hybrid model post-Covid-19 that can cater to the needs of a diverse language community. Yorùbá language speakers are promoting their cultural heritage and language within poetry and cultural circles, like the Nigeria Poet Association. The community empowerment approach of IBT to revive pride of the Torwali language, identity, and culture is also proving effective. This approach uses diverse tools and strategies, such as language literacy training, education in Torwali in early grades, advocacy for the rights of the people, cultural festivities, and folk poetry and music. They also participate in social gatherings, including funerals, marriages and traditional councils known as ‘yarak’, to further reach out to the public.

Other strategies include the development and sharing of resources, especially through platforms like YouTube. Odia speakers formed small groups of peer-to-peer knowledge exchange and shared available YouTube videos on digital safety and security. Dagbani Wikimedians and Twi language speakers use the same method to learn digital security, which is then disseminated and learned by others via verbal instructions and written texts. Since many members in Indigenous language communities speak and understand their language, but struggle to read or write it, educational video resources on platforms such as YouTube have made learning more accessible to activists.

Lastly, language activists are engaging in active counter-strategies to ensure they are prepared against digital attacks. This can be seen in how Igbo Wikimedians advocate for the use of Telegram groups — instead of Whatsapp — for collaboration due to security and privacy reasons. Gîkûyû language activists use Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) to protect their identities. Yorùbá activists, on the other hand, make an effort to implement two-step verification for their online accounts.

What’s next?

Across all the language communities, there is a consensus on the need for more access to digital security knowledge and capacity building on digital security. This can start with more recognition for Indigenous languages in digital security conversations. There is a need for more resources in these languages, including translations and localisations on digital security to ensure that native speakers are fully informed on the topic. The design of hardware and software, including interfaces and keyboards, also require inclusive technological approaches.

Governments should support regular security training interventions for the Indigenous language communities, and strengthen the legislation that protects users against all forms of online threats, including hate speech and misinformation. Civil society should create more awareness among the general public, build capacity, and sponsor digital literacy. Finally, to create a truly inclusive and equitable digital world, all stakeholders must work together to dismantle the digital oppressions that result in the exclusion of Indigenous language communities online.

More about Rising Voices’ Digital Security + Language research study:

The project points to the power of participatory research in surfacing the complexity of linguistic rights-related questions in the digital safety and security field, as each researcher approached the topic from a unique starting point in relation to their own experiences and understandings. f

This is the second blog post of a four-part series on Rising Voices’ Digital Security & Language research study that explored the intersection of digital security and linguistic rights in collaboration with 18 researchers, from 18 different language communities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Read the rest of the series: